The Queer Horror Aesthetic

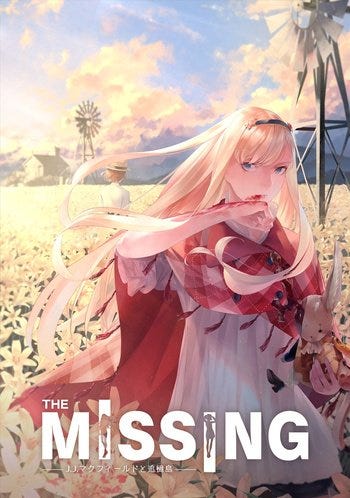

In 2018, the Japanese independent game developer Hidetaka “Swery” Suehiro released The Missing: J. J. Macfield and the Island of Memories under the publisher Arc System Works. The game itself was shrouded in mystery and its publisher put it out with little fanfare, while Suehiro himself was still working upon a much higher-profile game. Among its indie brethren, The Missing utilizes the prominent formula of side-scrolling puzzle platformers with horror motifs and environmental storytelling, one it shares with popular titles like Limbo or Little Nightmares. However, it twists this formula through the mechanic of the player character J. J. Macfield mutilating herself in order to navigate her environment, and this ability plays into the larger themes of self-harm. Most savvy horror fans could likely identify within the first hour or so the sort of tropes that The Missing implements. The antagonist is a shadow form of J. J. herself, the levels are surreal variations of locales from J. J.’s life, and the game relates bodily harm to mental anguish in a manner pioneered by the classic film Jacob’s Ladder (1990). What sets The Missing apart, though, is the identity of its titular character: J. J. Macfield is a trans woman.

The game that Suehiro is most well known for is the idiosyncratic Deadly Premonition. Many of its fans considerate it to be the most direct translation of David Lynch’s work to a video game, cribbing its characters and plot from the show Twin Peaks, while also invoking Lynchian themes of identity, repressed evil, and spirituality. Though the game itself was an overall technical mess, it garnered a cult following overtime thanks to all of its unique qualities spanning from the main character spouting film trivia for his alter ego to the designers modeling the world map off of actual north American towns. However, outside of just the genre of psychological horror, what does Deadly Premonition have in common with The Missing? Well, one of the strange characters you meet in Deadly Premonition is a deputy named Thomas with very obvious queer coding. Near the end of the game you suspect Thomas of being the killer, and you are pitted against them in a clock tower while they are dressed in women’s clothing. It is revealed later on that Thomas had not actually killed anyone and was only in love with the true killer, while Thomas is shown to be among the female victims of the killer identified as “goddesses of the forest.” It is left ambiguous as to whether Thomas was a trans woman, but it seems with The Missing that Suehiro wanted to interrogate his treatment of the character by creating a game explicitly starring a trans woman that is consistently empathetic to her struggles.

Japan is a complicated country in its relationship to LGBTQ+ people, so many were surprised by Suehiro’s insistence to not only include queer characters in his games, but to also make active attempts to try and evolve his understanding of said characters. Surprisingly, though, Suehiro is not the only creator to address queer perspectives in Japanese horror, and it is a more prominent theme in the genre than one might expect. Another interesting case is the game Rule of Rose, which was banned in the United Kingdom for depicting a lesbian relationship between its two female leads. Over the course of the game, the main character Jennifer discovers her past as an orphan who was forced to present as a male by her adoptive father, and a little girl from a nearby orphanage falls in love with her under the pretense that she is a boy. The rest of the game’s plot never denys continued romance after Jennifer began to present as a girl once more, and much of the game’s horror revolves around the subtle abuse of their environment and their codependent relationship. The imagery makes poignant references to the physical, emotional, and sexual trauma that destitute children receive from their caretakers, and which they reproduce in their own interactions with each other. Though it is arguable that much of the homosexual relationship is subtextual, it is clear that the themes are quite resonant with queer experiences.

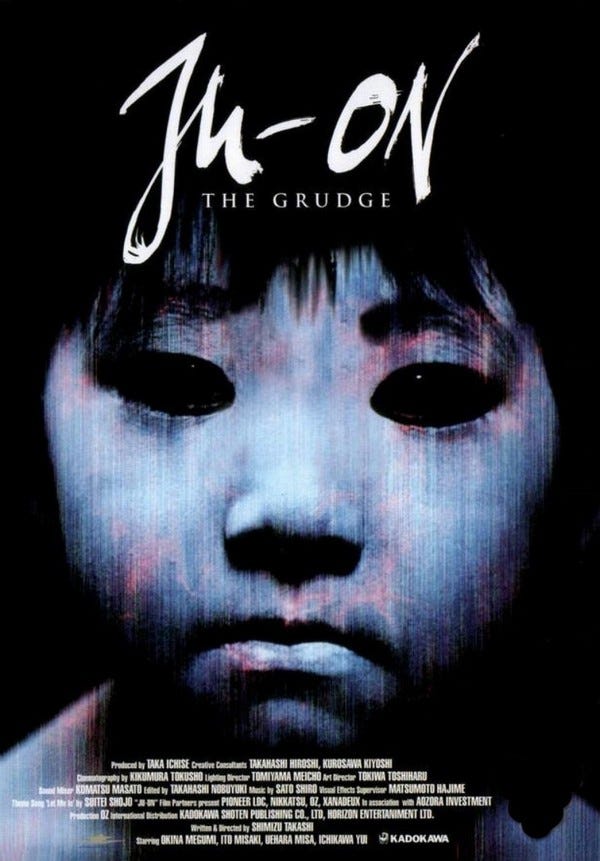

I believe that we can take works like The Missing and Rule of Rose as important illustrations of how, even when made in a traditionalist culture, the horror genre and its aesthetics can be utilized in favor of creating empathy for marginalized people. Perhaps Japanese horror even has a greater disposition to such narratives, because the tropes of Japanese horror focus more on vignettes of existential dread over mere conflicts between good and evil. The subgenre of J-Horror may have existed in some form or another since the advent of Japanese cinema, but only around the 1990s did its films really gain international traction. Ju-On: The Grudge (2002) and Ringu (1998) were two particular J-Horror films made on low budgets with digital cameras, yet they had such a devoted fanbase in America that both were remade by American studios in order to capitalize on their popularity. Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano, a Japanese-Canadian and professor in Japanese cinema, wrote about how this cinéma-vérité aesthetic might contribute to the unique appeal of J-Horror.

“The appeal of J-Horror films can be seen in their textual elements drawn from the urban topography and the pervasive use of technology, elements which are, at once, particular and universal. In the current post-studio climate, the conditions of low-budget and studio-less production are imprinted on new filmmakers work, especially regarding location shooting that frequently captures a sense of Tokyo urbanity. J-Horror has often effectively used this dense topography to represent a uniquely urban sense of fear to the possibilities of the megapolis and its mythos. The images of Tokyo and surrounding locales tied to the city-dwellers’ lives has been a significant motif in J-Horror” (26).

J-Horror films take advantage of both urban topography and residential architecture as a means to reinforce the fear of day-to-day life. The Grudge series specifically ties its story into this uncanny discomfort, as the ghosts that terrorize the victims of this “grudge” were once an average family that was slain in a bout of murderous domestic violence. The ghosts have an iconic design to them, sporting paperwhite skin and black eyes, a design that blends into the claustrophobic environment of an actual Japanese home. Over the course of the series, the ghosts become inseparable from the thin walls and tight corridors of the house itself, and it plants in your mind the suggestion that a wiry boy-phantom might be crouched down behind any door frame. There is no means to actually combat these entities, and the vengeance they dole out is as indiscriminate and brutal as a force of nature.

“The indispensable gadgets of urban life such as televisions, videos, cell phones, surveillance cameras, computers, and the Internet augment the anxious reality that J-Horror films produce. Various J-Horror films, including Ringu and the Ju-On series, play with the conceit of technological fluency. A character often becomes the target of an evil spirit by a mistaken belief in his or her ability to read the texts emitted from electronic devices that unexpectedly become conduits of spirits. Ringu’s sense of the horrific derives from the idea that the curse is disseminated through trans-media, such as Sadako crawling out of a television screen, a notice of death via telephone, and videotape functioning as a medium for transferring the curse to others. All of these cases have, as their basis in reality, the possibility of a destructive force spreading through media traffic like a computer ‘virus.’ Like an epidemic spiral, the more these everyday technologies are diffused, the more the horrific spreads along with them” (Wada-Marciano 28).

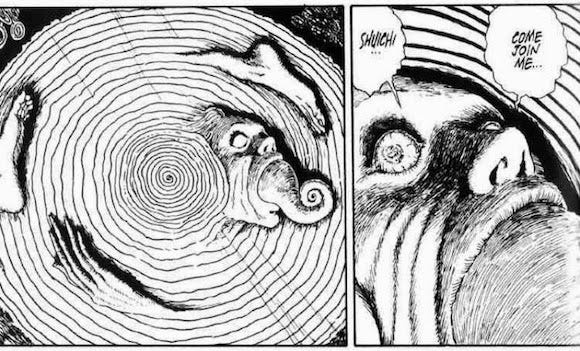

It is certainly notable that the tropes of J-Horror play upon the pervasiveness of technology and, ostensibly, the spread of information. Looking to another medium outside of video games and film, the prolific manga artist Junji Ito plays upon these themes through analogy in his seminal series Uzumaki. The story is composed of numerous horrific tales that are otherwise unrelated except for the ubiquitous mimetic image of a spiral. Each scenario is more bizarre than the last, escalating to the point of an entire village being subsumed into a dimension of infinite spirals and flesh. Ito has expressly stated that much of his inspiration for this story comes from the cosmic horror pioneered by Howard Phillips Lovecraft. However, even as Uzumaki adopts a familiar tone to Lovecraft’s fiction, its particular relationship with information and the unknown pointedly deconstructs the western ur-narrative of horror.

In many ways, the ur-narrative of horror has many similarities to Joseph Campbell’s ur-narrative of the hero’s journey. No single story fits either formula perfectly, and there are infinitesimal deviations on the standard form, but they are ultimately useful to understand the ideas such narratives are meant to impart. The art philosopher Noël Carroll establishes a blueprint for horror stories in his book “The Philosophy of Horror: or Paradoxes of the Heart,” a blueprint that I plan on utilizing in this essay and eventually deconstructing. Carroll asserts that the genre of horror, existing independently from science fiction or fantasy from the 18th century onward, relies upon the dramatization of discovery and subsequent understanding of the unknown. He sets out a series of stages for what he calls the “discovery plot,” which are as such: (1) onset (2) discovery (3) confirmation (4) confrontation. Along with these stages, Carroll proposes that a horror narrative requires some form of monster, that both poses a threat and appears categorically impure to rational sensibilities, in order for the story to specifically cement itself as a work of horror.

“Werewolves, for example, violate the categorical distinction between humans and wolves. In this case, the animal and human inhabit the same body (understood as spatially locatable protoplasm); however, they do so at different times. The animal and the wolf identities are not temporally continuous, though presumably their protoplasm is numerically the same; at a given point in time (the rise of the full moon), the body, inhabited by the human, is turned over to the wolf. The human identity and the wolf identity are not fused, but, so to speak, they are sequenced. The human and the wolf are spatially continuous, occupying the same body, but the identity changes of alternates over time; the two identities — and the opposed categories they represent — do not overlap temporally in the same body. The protoplasm is heterogeneous in terms of accommodating different, mutually exclusive identities at different times” (46).

Carroll establishes the impurity of monsters as arising from the principles of interstitiality and categorical contradictoriness. Much like nuclear science, he divides the two major embodiments of these principles into “fusion” and “fission.” Fusion entails either the combination of two or more mutually exclusive creatures (such as a capuchin monkey and a vampire bat) or the introduction of non-standard characteristics to a singular creature (such as ants that are both giant and radioactive). The description of werewolves that Carroll provides is a good example of fission, where a monster’s identity is separated along temporal, spatial, or metaphysical planes. I would like to note here that there is an inherent notion of identity to Carroll’s monsters that will be important to reference later on. Meanwhile, let us examine how these standards apply to the freaks of Junji Ito’s design.

Uzumaki appears to have many monsters that fall well into both of Carroll’s categories of fusion and fission. In terms of fusion, there are the snail people that slowly transition from human beings into humongous gastropods, as well as the mosquito women that drink blood through metal siphons in order to feed their larvae. In terms of fission, Ito has women with inhumanely long curls that seem to take on a mind of their own, as well as a lighthouse that is revealed to have an infinite internal staircase that should reach way further than its external dimensions. However, what is the central monster that persists throughout the chapters of Uzumaki? It is clear that the animating force is the image of the spiral itself, and it is this image that the townspeople continuously find themselves fusing with, and it seems that this image exists in infinite variations not limited by time, space, or the very laws of physics. The spiral is the central thesis of Uzumaki, and all the interstitial transgressions characters make come from an undying obsession with the image.

Over the course of his book, Carroll argues that the reason why people are so fascinated by what he deems as “art-horror” is the cut that monsters create in ontological understanding. He explores this line of thinking by attempting to resolve the two primary paradoxes of horror. The first paradox exists as such: how can an audience experience real fear at the prospect of monsters which they know to be fictional? Carroll addresses this paradox by first problematizing the assumption that emotions such as fear must be predicated on immediate experience, as it is clear that different individuals can possess numerous physiological responses to the same stimulus that they only later interpret as being evident of one emotion or another. Because of this, he believes that an audience can be legitimately afraid of fictional scenarios since they can think themselves experiencing such a scenario, just as they can be afraid of an actual scenario of horrific encounters even if they have not experienced it personally. The second paradox is one he refers to as the “paradox of the heart,” and it goes as follows: why would an audience indulge in art that exhibits grotesque imagery and elicits negative emotions? Carroll concedes that there may be many reasons why different subgenres of horror resolve this impasse, but he also believes that there is a general reason why horror as a genre overcomes the problem. In both narrative art and non-narrative art, there is a mystery posed by the unknown that people must solve even if the target of their inquiry thoroughly disgusts them.

“The disclosure of the existence of the horrific being and of its properties is the central source of pleasure in the genre; once the process of revelation is consummated, we remain inquisitive about whether such a creature can be successfully confronted, and that narrative question sees us through to the end of the story. Here, the pleasure involved is, broadly speaking, cognitive. Hobbes, interestingly, thought of curiosity as an appetite of the mind; with the horror fiction, that appetite is whetted by the prospect of knowing the putatively unknowable, and then satisfied through a continuous process of revelation, enhanced by imitations of (admittedly simplistic) proofs, hypotheses, counterfeits of causal reasoning, and explanations whose details and movement intrigue the mind in ways analogous to genuine ones” (Carroll 184).

To be clear, I agree with Carroll on this point, I think people largely enjoy horror like Uzumaki because they have an innate intellectual curiosity that is triggered by Ito’s macabre depictions. Still, I think it is useful to apply Carroll’s stages of discovery to the plot of Uzumaki in order to see how it obeys, diverges from, and subverts this structure. The first stage (1) is the onset, which in Uzumaki would be the potter who becomes more and more obsessed with the spiral until he contorts his own body into an impossible spiral. The second stage (2) is the discovery proper, which comes to the male protagonist when his mother kills herself trying to gouge out her own cochlea, and comes to the female protagonist when her hair begins to take on an aforementioned mind of its own. The third stage (3) is the confirmation, which occurs gradually as more townspeople link all of the strange events to the spiral symbol, culminating in the spiral galaxy that comes into view throughout the night sky. The fourth stage (4) is the confrontation, when the male and female protagonist realize that the town is doomed, and so they try (and ultimately fail) to escape the town together using what they know about the spiral curse.

Carroll’s schema for narrative-horror is primarily focused on the interplay of information, while Wada-Marciano identifies information as a vector for the supernatural in J-Horror. Uzumaki follows Carroll’s stages rather well, but it is the visual information of the spiral itself that has supremacy over human cognitive capacity. Junji Ito adapts the Lovecraftian tropes of cosmic horror for his series, translating the concept of someone “going mad from the revelation” to a visual context. It subverts the ur-narrative of horror by exhibiting that, not only does the curse consistently evade comprehensive understanding, but the information that the characters do possess erodes both their sanity and their humanity. If people look to horror as a genre in order to satisfy their sense of curiosity and mend an insecurity in reality, then Uzumaki denies them any resolution. The final pages of Uzumaki shows the hellscape of flesh and spirals consuming the two protagonists along with the rest of their town, providing closure only in the two consummating their love through their intertwining bodies.

Now, none of this is to say that the ur-narrative of horror has no place in the genre, nor is it to say that J-Horror always subverts it or is the only form to subvert it. J-Horror is no more predisposed towards emancipatory or reactionary themes than western horror subgenres, as Carroll continually points out. What I do think, though, is horror that is pervasive, unknowable, and mimetic creates certain potentials not present in horror that is temporary, explicable, and essentially physical. Stories like The Missing and Rule of Rose would not be possible if the horror genre was limited to strict adherence with Carroll’s stages. While his work is effectively instructive to the horror genre, he uses a structuralist lens that tends to disdain critical theory and readings via analogy. If we are to realize the queer potential in horror, then we cannot rely on his theory alone, as it is necessary to first confront the heteronormative and oppressive narratives that pervade much of the genre.

“Horrific beings, that is, do not contravene cultural norms at any level that marks a political difference between the dominant status quo and those it putatively represses. Neither eating human flesh nor denying the difference between insects and humans is on the political agenda of any liberation movements that I know of. Challenging cultural norms, then, at this level of abstraction, does not touch the political foundations of a social order, and, consequently, reasserting these norms would have no significance with respect to reconfirming the political status quo.

“Another way to get at this point is to notice that there may be a slide in the account between two notions of the ‘normal.’ On the one hand, ‘normal’ may be seen to refer to the norms of our classificatory and moral schemes. On the other hand, ‘normal’ may refer to the ethos and behaviors who unquestioningly conform to some vision of (culturally, morally, politically) complacent middle-class life — the organization man, the moral majority, the silent majority, etc. The ideological account of horror under examination seems to move from the observation that horrific beings are abnormal in the first sense of the term, to the view that their defeat reasserts normality in the second sense of the term, which, of course, is a sense that would be relevant to certain aspects of contemporary cultural politics. But this surely rests on simple equivocating over certain meanings of normality” (Carroll 203).

The major assumption that Carroll makes here, which I seek to contest, is that there is a definite line of distinction between these two categories of “normal.” First off, Carroll must realize that monsters often have certain qualities that do “contravene cultural norms,” as he himself has chronicled the pervasive characterization of vampires as bisexual. Second, even when we observe certain behaviors that should be disgusting to a universal moral standard, those which violate his primary notion of “normal,” he fails to recognize the historicity such taboos possess. Cannibalism has long been used as an ideological tool of settler-colonialists, fabricating cases of such a practice within indigenous communities in order to justify “civilizing” said individuals. George Romero’s classic Living Dead trilogy made zombies into a household monster, but the films themselves comment on the racism stemming from zombies as a bastardized appropriation of Haitian mythology. Before Night of the Living Dead, a black man would not have been the protagonist, he would have been the monster.

Ideology is much more insidious than what Carroll relates, as no single piece of art would actually fit into the mould that he sets out as his secondary definition of “normal.” Ideology does not work in terms of singular positions that gauge our relative political correctness, but coercive narratives that one can easily reproduce regardless of whether they are an outright fascist or an adamant liberal. The point of analogous readings that are used in critical theory is not to paint an entire genre as a monolithic edifice of a singular ideology (though I will admit that this can occur), because these readings are meant to identify the narratives that are generally reproduced within said genre, regardless of intent. Cultural philosopher Slavoj Zižek writes that ideology is generally unconscious, and its maintenance requires a fetishistic reification of what it establishes as prima facie real.

“As to the idea that Ideologiekritik is no longer operative in today’s conditions of cynical fetishism, since the fetishist ideology lacks the tension between surface and depth that opens up the space for critico-ideological unmasking (‘things are not what they seem’), I claim that the fetishist transparency is false: what gets lost in it is the fetishist belief itself. For example, concerning commodity and money fetishism, if we read Marx carefully, we see that the fetishist does not claim that money is a special mysterious object; for the fetishist, money is just an object that materializes a set of social conditions, and this is what money effectively is. What the fetishist does not see is not the ‘real state of things,’ but the fact that he himself, in his social activity, acts as if he believes in the fetish, as if money is a special magic object” (648).

Zižek points out that ideology often has little to do with intent, while it has everything to do with performance. Fetishization flattens out ideology not in a way that conceals the truth, but in a way that conceals the narrative through which the Real is transformed into ideology. Carroll effectively fetishizes the idea that horror is apolitical, not because he is wrong in his assessment that horror as a genre has no specific ideological bent, but because he uses this truth to conceal how horror is useful for communicating certain ideological narratives. Carroll can understand that monsters constitute some form of positive identity, as he alludes to with his description of “fission,” but he leaves the symbolic meaning of such identities at the waist side. In all honesty, I think there is a meaningful similarity between Zižek’s lacanian analysis and Carroll’s horror schema, even if Carroll himself is not privy to it. Horror introduces anxiety into the ideological fantasy that there is the Real behind the mask of reality, and this anxiety is defeated before it can unmask the Real. Horror like Uzumaki is more unsettling because it plays out the unmasking of the Real, and what is found beneath is nothing, not even the absence of the Real.

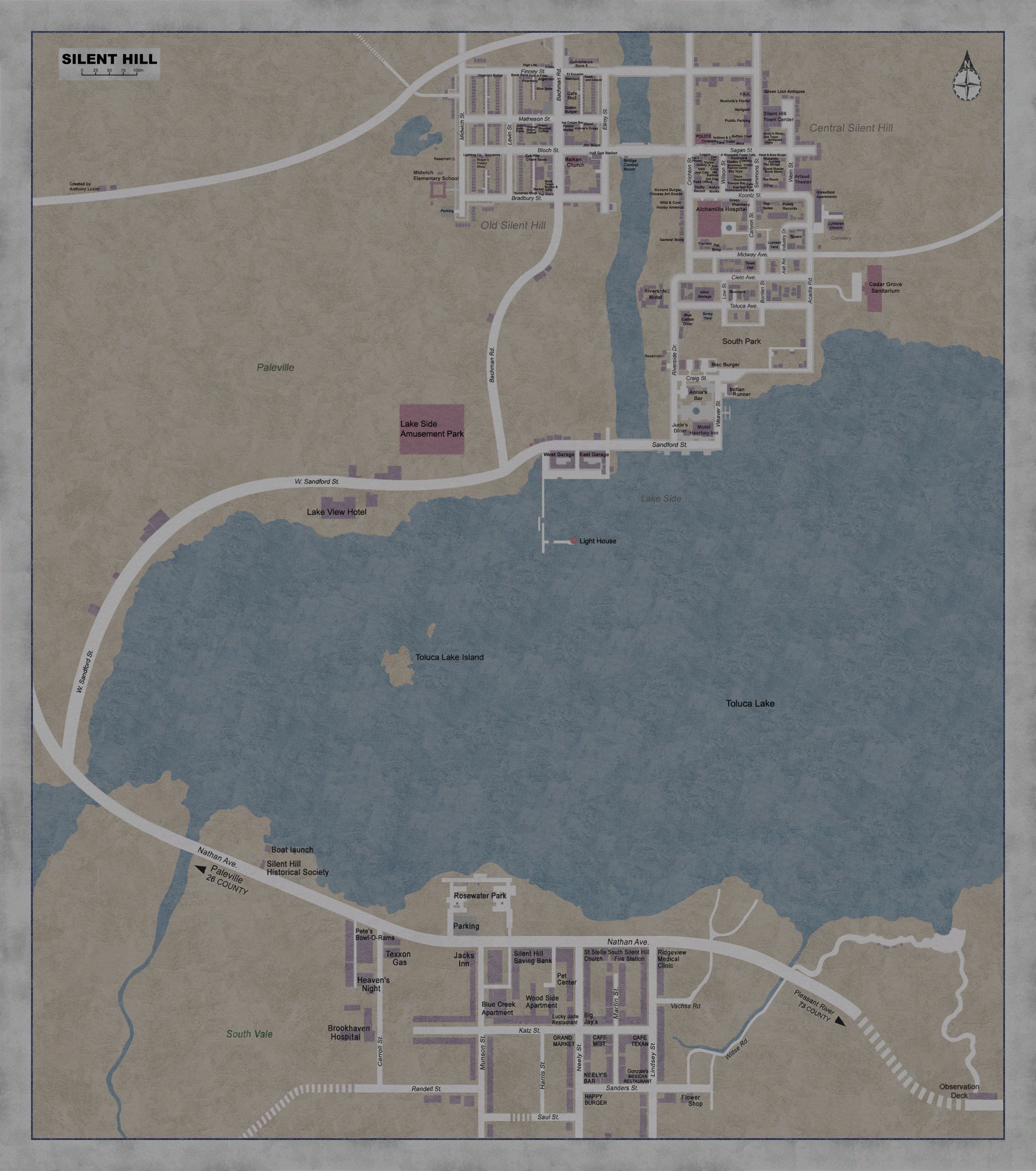

Let us step away from the impulse to analyze all horror media within literalist terms. It is infinitely useful to understand the tropes and mechanisms that make up the genre, but these things become immaterial once they are divorced from historical contexts. Horror, in all of its forms, is an iterative genre, and as such there are certain motifs that are repeated ad infinitum. For example, Silent Hill 2 is largely considered one of the best survival horror games ever made, if not one of the best video games in general. The plot structure and themes of the game are largely inspired by the work of American creators like Stephen King. The game explicitly references this through naming streets in the eponymous town of Silent Hill things like Bachman Rd., Bradbury St., or Koontz St. . Even critically acclaimed works of horror will wear their influences on their sleeves and, as such, it is even more important to analyze the history that surrounds any given piece.

In critical theory, there is a concept known as “coding,” where a character that is not explicitly characterized as part of a marginalized group is drawn with characteristics widely associated with that group. For the purposes of this essay, I will be focusing on the specific subspecies of queer-coding, which became a mainstream practice in response to the infamous Hays production code. Filmmakers within the studio system were prohibited from explicitly involving homosexual characters in their productions, and any act of what had been deemed “sexual degeneracy” could not be shown in a positive light. In cases where filmmakers wanted to tell queer stories, they adopted visual shorthands like two men touching their cigarettes together as an analogy for intimacy, until the point where they created an entire language of decipherable codes. Audiences were meant to understand these codes, but creating such a lexicon also constitutes the trappings of language, and many forms of media exploit coding as a means to reinforce heteronormative narratives with plausible deniability. Now, long after the Hays code has withered away, we still see numerous examples of effeminate male antagonists juxtaposed against male protagonists that embody hegemonic masculinity.

When vampires are not explicitly homosexual, as with stories like “Carmilla,” they are drawn in broad strokes with numerous queer-coded behaviors. Not all vampires are associated with queerness, for even Karl Marx uses them to characterize the bourgeois, and films like Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1974) paint vampires as representatives of the dual forces of patriarchy and economic exploitation. However, it is undeniable that there exists a pervasive, reactionary narrative that is built into the identity of the vampiric monster. The vampire is a predatory homosexual, one that looks to tempt the pious heterosexual man or woman into a realm of forbidden pleasure. Vampires are sadists, they are decadent, they are dead in the sense that Jouissance, a french term for orgasm, is the little death. When we do have sympathetic portrayals of vampires, such as The Lost Boys (1987), they are usually unassuming youths that have fallen to the whims of a grand manipulator. Therein lies the fantasy that undergirds conversion therapy, that one can simply excise the corruption through an external form in order to revert the lost back to “normal.”

I think it would be useful, here, to take a closer look at the relationship between the protagonist Michael and the antagonist David in The Lost Boys. Many have characterized their relationship as homoerotic, for it seems that David’s primary motivation throughout the film is to turn Michael into a vampire and have him join his gang. Michael is the all-american teenager, rebellious in the James Dean sense, but ultimately loyal to his family. He is tempted by the freedom that David offers, a life independent from suburban mundanity, but he rejects it once he has gotten that impulse out of his system. The Lost Boys could easily be an 80’s, gender-swapped adaptation of “Carmilla,” if not for the ostensible female love-interest Star. Her role in the film is decidedly passive, as she first acts as a surrogate for David’s will until the point where she betrays him, and after that point she is saddled with a vampiric child to look after. This is not to say her character is bad per say or that she should be removed from the film, but the ultimate role she plays in the narrative is questionable. I do not think that the story would be better if Star was made to be a Jezabelle-esque character, but, as is, her and her ward seem to clash with both the ideals and makeup of David’s gang.

Judith Butler uses the psychoanalytic concept of melancholia in order to characterize a specific form of homosexual melancholia. The compulsory heterosexual edifice not only prohibits one from mourning the death of a homosexual desire, but prohibits one from mourning the very possibility of a homosexual desire. Thanks to this prohibition, the grief that is repressed unconsciously manifests itself in stories that play out the death of a homosexual desire under a thin heterosexual veil. Star plays as the mediator of Michael and David’s relationship in The Lost Boys, allowing the possibility of homosexual attraction to exist in a quantum state, up until the point that David is killed and Star’s role is no longer necessary. Perhaps this explains why many queer people identify with vampire stories like The Lost Boys, as they allow the viewer to perform a homosexual desire by assuming Michael’s role without removing the veneer of conscious heterosexuality. Butler herself acknowledges the power hidden in such visceral readings, and the political potential when one iterates upon these performances.

“In saying ‘I love you,’ a certain ‘I’ is installed in one of the most repeated phrases in the English language, a marketed phrase, one that belongs to no one and to anyone. One risks a full evaporation into an anonymous citationality: I speak as countless others have spoken, say the same words, and you are equally substitutable at such a moment. On the one hand, the citationality of the speech act offends our sense of singularity or even authenticity, if that is a value we have. On the other hand, it is precisely through the citationality of the speech act that the body emerges in a specifically linguistic form. I give some somatic feeling to you, or try to, when I say these words, and I want the words to carry that feeling from here to there to find its destination with you, and to be received there, or even to alter who you are and what you feel” (237).

Of course, what Butler is addressing here are certain speech acts that work as performances conveying the feeling of love, not performances conveying the feeling of fear. I think most can intuitively understand the purpose of conveying queer love through the recreation of love stories, as such stories provide a common ground with which to cultivate empathy. The problem, though, is that queer people have a full range of emotional experiences that are just as vibrant as the range of a cis-heterosexual individual. If queer people are only represented in the realms of romance, comedy, or tragedy, then it can create the impression that queer people are exceptionally baroque. Moreover, queer people already have a place within the horror genre, but that place is with the object that is meant to be feared, not the subject one is meant to identify with. There are examples of artists attempting to reclaim queerness in horror, and not bust to swap a queer character into a heteronormative narrative, but in ways that deconstruct the narratives of horror we have been accustomed to.

There is a certain independent game that I want to call attention to, a horror game called We Know the Devil. It is styled in the format of a visual novel, focusing on the interactions between characters and centering gameplay around what choices you make to affect the course of the plot. The setting is a christian camp with a magical realist bent: it’s where the “bad” kids are sent, God talks to you over the radio and informs you of all your inadequacies, and you have to stave off the devil from possessing you. We Know the Devil is quite aware of what it’s doing here, and the three main characters you focus on are all some form of queer femme. There are three endings in which you build up the relationship between two of them, and the one who is left out transforms into a monsterous manifestation of their own inhibitions that you must oust. The fourth ending is where the real subversion of expectations takes place, for when you build the relationship up equally between them all, none of them are saved, and instead they embrace each other in their monstrous forms and destroy the camp.

Considering one of the three characters, known as Venus, we only truly understand her once we achieve the fourth ending. She is a trans woman, and the game will use male pronouns for her up to the point where she comes to terms with that fact. The process that the characters undergo in the three prior endings are typical, for they allow the characters to play out their queer fantasies, but ultimately require the sacrifice of one of them in order to return to “normal.” This is the purpose of the camp, it is itself an analogy for the patriarchal and heteronormative edifice, and it needs a queer other in order to properly contextualize itself. It is only when Venus rejects this process, when she allows herself and her friends mutual acceptance, that they gain the power to overthrow the oppression borne down upon them. They are only monsters from an incomplete perspective, when their fears and desires are externalized against their wishes, but viewed as a whole they bolster their unique identities. The devil is a thing to be feared, for the devil is transgression, but the devil can also be beautiful if we embrace it with strength.

Fear is a very peculiar emotion, because fear is inexorably tied with oppression. Fear is manifest through acts of explicit violence, ranging from individual murders to historic massacres, all of which are meant to scare a particular group into submission. There is also fear in more subtle and systemic forms of oppression, such as the double bind where a queer person must either be in the closet and fear being discovered, or be out of the closet and fear being discriminated against. Both the oppressed and the oppressors are afraid of each other, but whereas the oppressed are afraid of the oppressors’ recurrent power, the oppressors are afraid of the oppressed discovering power. The oppressors want to sustain that climate of fear indefinitely, even if they do attempt to conceal it at times, while the oppressed want to destroy that climate altogether. This is why horror stories that compliment power see monsters coming to disrupt the status quo, while horror stories that subvert power see that the status quo is itself the monster.

In order to round out this essay, I want to discuss the ontological distinctions between fear caused by real stimulus and fear caused by art-horror. Specifically, I want to frame these distinctions in terms of the deterministic vs. stochastic debate around free will. Noël Carroll’s answer to the first paradox he proposes is notably skeptical of deterministic interpretations of fear responses. Determinism thinks that free will is false, for humans are animals that are ultimately predetermined by their basal instincts, and if free will is anything then it is an illusion conjured up through evolutionary psychology. In terms of horror, it follows that an audience does feel genuine fear when they view art-horror, because horror media triggers unconscious impulses that exist independently from one’s ability to distinguish reality and unreality. The issue with this interpretation, though, is that people do not react as if the events of the story are actually happening or as if they were threatened by a predator, for if that were the case they would jump out of their seats and flee from the theater. People do not engage with horror in a way that overrides their higher cognitive functions, and, in fact, many can be intellectually stimulated while also being afraid.

Carroll is not a pure stochastic either, and he rejects the idea that the fear one exhibits in response to art-horror is simply play-acting. He sets about refuting this interpretation by illustrating a hypothetical scenario where someone relates to you an emotionally wrenching story, one that causes the hair on your arms to bristle, and then this person informs you that they had made the story up. This raises the question as to whether your fear, let alone physiological reaction, was faked because you now retroactively understand the story to be fictional. Carroll doesn’t think so and I don’t think so, because whether or not the scenario was fiction or nonfiction you still had a visceral reaction to it. The problem with both the deterministic and stochastic approach is that they both assume a sort of ontological rigidity to the line between reality and unreality. The thing is, the founding premise of horror is that the unreal has crossed into reality.

Both transgressing and blurring the lines of possibility, these are essential factors of any queer identity. Being a queer person myself, I am particularly interested in genres like horror, magical realism, and urban fantasy because they all require their audiences to at least entertain the possibility that common sense is not objective truth. Once we can entertain fictional alternatives, this opens up the possibility for us to interrogate the ideological narratives that we are bombarded with every day. I chose to focus on horror in this essay because I have a unique relationship with the genre as someone who writes in it, and because I have observed many promising examples of queer stories positively told through horror. While I don’t consider all the pieces I cite here to be focusing on queerness, I do think every work I cite is worth your time to experience yourself, including Noël Carroll’s book. Many refuse to consider horror as a genre that should be taken seriously, and many refuse to take queer voices seriously, so in mutual marginalization we find the means to create mutual aid.

Butler, Judith. “Response: Performative Reflections on Love and Commitment.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 1/2, 2011, pp. 236–239. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41290296. 16 Feb 2019.

Carroll, Noël. “The Philosophy of Horror: or Paradoxes of the Heart.” Routledge 1990. Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc. Abingdon, United Kingdom.

Deadly Premonition. Access Games. JP: Marvelous Entertainment. WW: Rising Star Games. Playstation 3, 2010.

Ito, Junji. “Uzumaki.” Shogakukan. Viz Media. JP: Big Comic Spirits. EN: Pulp. 1998–1999.

Jacob’s Ladder. Directed by Adrian Lyne, TriStar Pictures, 2 Nov. 1990.

Ju-On: The Grudge. “呪怨じゅおん.” Directed by Takashi Shimizu, Lions Gate Films, 18 Oct. 2002.

Night of the Living Dead. Directed by George A. Romero, Image Ten, The Walter Reade Organization. Continental Distributing, 1 Oct. 1968.

Ringu. “リング.” Directed by Hideo Nakata, Ringu/Rasen Production Committee. Toho, 31 Jan.1998. Adaptation of “Ring” by Koji Suzuki.

Rule of Rose. Punchline. JP: Sony Computer Entertainment. NA: Atlus USA. Playstation 2, 2006.

Silent Hill 2. Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo. Konami. Playstation 2, 2001.

The Lost Boys. Directed by Joel Schumacher, Warner Bros., 31 July. 1987.

The Missing: J. J. Macfield and the Island of Memories. White Owls Inc. Arc System Works Inc. Japan. Steam Version, 2018.

Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo. “J-HORROR: New Media’s Impact on Contemporary Japanese Horror Cinema.” Revue Canadienne D’Études Cinématographiques / Canadian Journal of Film Studies, vol. 16, no. 2, 2007, pp. 23–48. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24408470. 13 Feb 2019.

We Know the Devil. Date Nighto. Steam version, 2015.

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders. “Valerie a týden divů.” Directed by Jaromil Jireš, Janus Films (U.S.), 16 Oct. 1970.

Žižek, Slavoj. “Our Daily Fantasies and Fetishes.” JAC, vol. 21, no. 3, 2001, pp. 647–653. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20866430. 14 Feb 2019.